V

irginia

C

apitol

C

onnections

, S

ummer

2015

4

The tea party. Or is it the tea

party movement? Or, is the tea party a

movement, a faction, or something even

less defined, like a body of ideological

energy within conservatism?

Or maybe it is best described as simply

the tea party wing of the Republican Party.

However it is labeled, the tea party—

as amorphous a group as there is in

Virginia politics today—proved once

again during the June 2015 primaries just

how vexing it can be to Republicans. What

its supporters hoped would be a triumphant march to near-total

domination of the Republican Party with the slaying of Speaker

Bill Howell and several other too-moderate incumbents, turned out

to be a humiliating series of losses, instead.

Howell easily fended off Susan Stimpson with 62% of the vote.

Emmett Hanger, who incensed many Republicans by supporting

Medicaid expansion, got 60% in his intra-party match against Dan

Moxley. John Cosgrove got 65% against Bill Haley. The tea party

even lost a couple of incumbents, with Mark Berg losing in House

District 29, and Democrat Johnny Joannou losing in House District

79.

Yes, you read that correctly: Democrat Johnny Joannou. The

Joannou loss is stunning if only because with the exception of a

few years, Joannou has been in either the House or Senate since

1976. But the tea party angle to the story is interesting: in the

closing days of the race against Steve Heretick, the Portsmouth Tea

Party endorsed Joannou and encouraged its members not only to

vote for him, but also to volunteer for his campaign and work the

polls for him.

The only real win for the tea party was in the 11th Senate

district, where Amanda Chase knocked off incumbent Steve Martin.

So why did the tea party perform so poorly in this year’s

primaries? Tea party leaders misread the electorate leading up to

the primaries, and misunderstood their ability to shape the voting

behavior of tea party-minded supporters. The Howell-Stimpson

race perhaps best exemplifies these mistakes. Many in the tea party

wing of the Republican Party assumed (or hoped) that there was

a deep well of pent-up frustration among the tea party-minded

primary voters, and that they would behave in June 2015 like

they had behaved in June 2014 in the 7th congressional district

race between then-House Majority Leader Eric Cantor and then-

unknown Randolph-Macon College economics professor David

Brat. In that race, Brat tapped into a deep well of voter frustration

and walked away with a surprise upset of Cantor.

Post-election analysis of the Cantor-Brat race generally

concluded that tea partiers rebelled and threw Cantor overboard

much like their inspirational forefathers threw chests of tea

overboard in the Boston harbor 242 years ago.While there certainly

is a lot of truth to this, there was also a lot of anecdotal evidence

of general voter frustration that Cantor had lost touch with his

district, took too much for granted, and didn’t spend time doing

the constituency service that he should have been doing. Many

Republican voters after-the-fact, expressed remorse at the Cantor

loss. Many of them said they wanted to send Cantor a message, but

never thought he would lose the race.

Everyone was caught off guard by the Cantor loss. But the

take-away lesson for tea party-minded Republicans was that

there was a largely unseen segment of the Republican electorate

ready to do across the state in June 2015 what they did in the 7th

congressional district in June 2014. They were the silent majority

among Republican primary voters. Seen through the analytic

framework of the Cantor loss, all that needed to be done for the

2015 primaries was to offer up tea party-friendly candidates, and

the results would inevitably follow.

It was a field of dreams strategy, but the masses of angry voters

simply did not materialize from amongst the corn stalks. The

problem is, tea party-minded voters are much more energized by

federal issues than they are by state issues. The tea party movement’s

roots are in anger over the Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP),

bailouts of big banks by the federal government, rising federal

deficits and federal budgets that don’t balance, and in the cozy

relationships that big business has with elected officials in both

parties in Washington. The fundamental misread of the electorate

was that this federal-level anger could be channeled into state-level

anger, at a legislator’s support for a transportation funding bill, or a

general tax increase, and produce the same results.

Speaker Howell’s position has been strengthened by not only

the decisiveness of his win, but in how he ran his campaign. He took

the challenge seriously. He campaigned hard against Stimpson. He

reminded voters in his district why they had reelected him so many

times. Senators Hanger and Cosgrove did similarly in their wins.

But while the June primaries were a big win for the establishment

wing of the Republican Party, obituaries for the tea party wing are

not yet in order. In fact, a big battles looms, and it will be over

how Virginia Republicans will select their presidential candidate:

primary or convention. This question will tell just how much power

Speaker Howell and the rest of the establishment wing gained from

their primary wins.

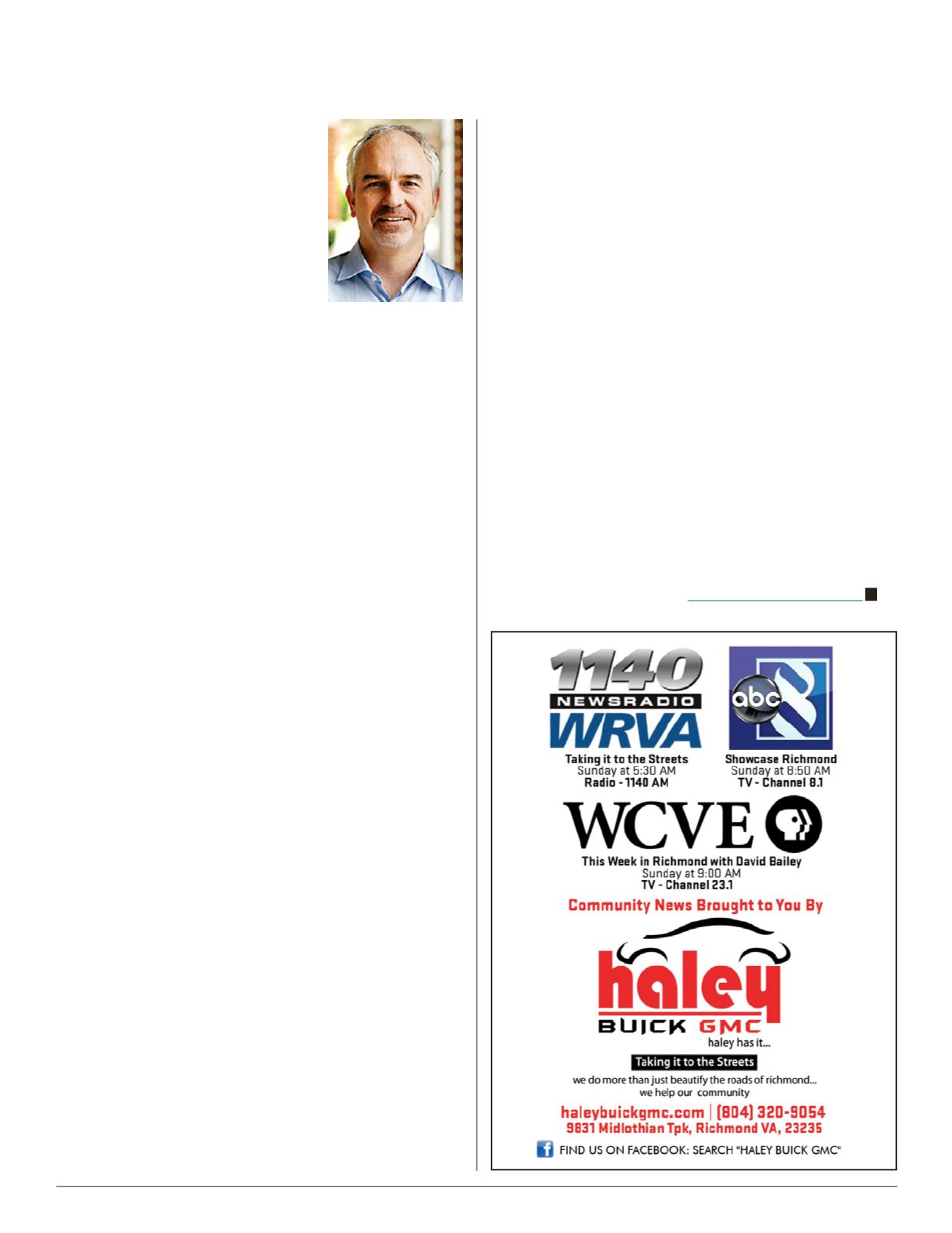

Dr. Quentin Kidd, Vice Provost and director of the Judy Ford

Wason Center for Public Policy

http://cnu.edu/cpp/index.aspThe tea party?

By Quentin Kidd

V